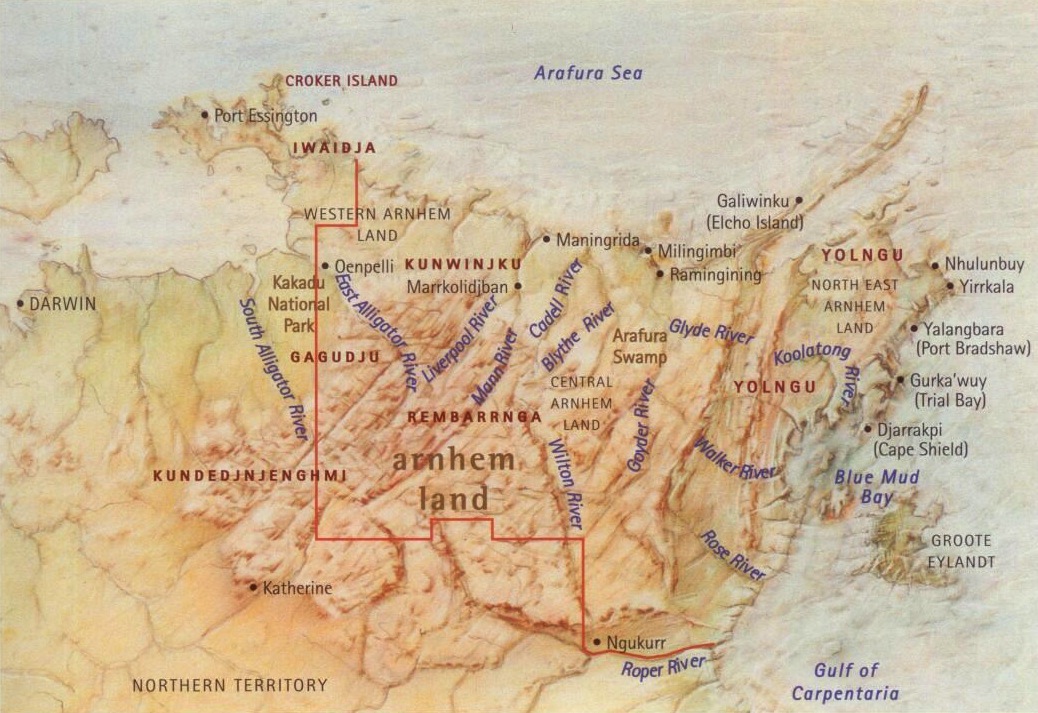

Northern Australia is characterised by diverse topography, from forests, lagoons, rivers, mangroves, flood plains, rocky escarpments, coastline and islands. One of the most remarkable and substantial features is Arnhem Land, which is located in the Northern Territory bounded on the west by Kakadu National Park, the north by the Arafura Sea, the east by the Gulf of Carpentaria and in the south by the Roper River. It is a vast area covering nearly 100,000 square kilometres. Physically, Arnhem Land is comprised of a spectacular plateau which is penetrated by freshwater rivers, dotted with waterlily strewn billabongs, rocky outcrops, patches of dense woodland, plains of spear grass and lowlands which are subject to radical transformation during the wet season.

Image: Map of Arnhem Land © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2013. This

product is released under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence.

Languages and Clans

Language groups across Arnhem Land are diverse and include Bininj Kunwok, the language group of West Arnhem Land and the predominant dialect Kuninjku (eastern Kunwinjku) to the west. The language groups of Central and Eastern Arnhem Land comprise Rembarrnga; Gumatj, Rirratjingu, Djapu, Manggalili, Marrakulu, Madarrpa, Galpu, Dhalwangu, Dätiwuy, Ngaymil, Djarrwark, Munyuku, Djambarrpuyngu, Wangurri, Dhudi-Djapu and Gupapuyngu.

Historically, Arnhem Land was roughly divided into three sections, Western, Central and Eastern. An imaginary line drawn from just west of Maningrida directly south to, and over, the Wilton River and then running west between Pine Creek and Katherine, sets out Western Arnhem Land, while a line west of Elcho Island running south, east of Donydji to Blue Mud Bay, Gulf of Carpentaria, identifies Central Arnhem Land and reveals Eastern Arnhem Land as rather like a peninsula.

Yet, Helen Groger-Wurm in her volume Australian Aboriginal Bark Paintings and their Mythological Interpretation, 1973, sites Arnhem Land into a small Western Arnhem Land and a substantial large Eastern Arnhem Land.1 However, today these subdivisions are not strictly adhered to, particularly due to the complexity of linguistic and cultural groups. While Western Arnhem Land and Eastern Arnhem Land culturally and linguistically are clear, Central Arnhem Land has a higher density and mix of linguistic and cultural groups centred around Maningrida. The communities of Western Arnhem Land are generally considered to be Gunbalanya (Oenpelli) Jaruluk (Beswick), Bamyili and Katherine.

The Roper River originates near the Stuart Highway flowing to the Gulf of Carpentaria along the southern boundary of Arnhem Land. As the Roper River snakes its way towards the Gulf, it snuggles against the tiny community of Ngukurr, a former Anglican mission which is located on hilly ground overlooking the river. Ngukurr was established early in the 1900s on the north side of the Roper while the only access road was on the south side, resulting in the community being isolated during the wet season months. Access during the Wet season, today is only by air or boat from Roper Bar. Many of the southeast Arnhem clans living at Ngukurr, have traditional country to the south of the Roper. During the dry, Ngukurr is accessible by road from Katherine and Darwin.

The numerous clans from the surrounding region include seven language groups, the Mara, Ngandi, Alawa, Nunggubuyu, Rittarrngu, Wandarang and Ngalakan.

The numerous clans from the surrounding region include seven language groups, the Mara, Ngandi, Alawa, Nunggubuyu, Rittarrngu, Wandarang and Ngalakan.

Ayangkulyumuda (Groote Eylandt) is renown for the exquisite bark painting of suspended subjects, such as Dinungkwulanguwa (dugong)2, set against an iconic black manganese background created with a delicate combination of red, yellow and white executed through dashes, dots and lines.

Minjilang, formerly Mission Bay, is located on Croker Island, some 235 kilometres east northeast of Darwin. It is the central point on Croker Island, supported by eight small family outstations. The island is just a few kilometres from the Cobourg Peninsula on the mainland. Miljilang’s population include Yarmirr people, some speak Iwaidja and are the only speakers of this language, but English, Gunwinggu and Maung are also spoken. Croker Island also offered a safe haven to many children from the Stolen Generation. 3

Image: MUNGURRAWUY YUNUPINGU c.1907-1979, Macassan Traders, 1968, natural pigments on bark, © the artist, courtesy Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre.

Milingimbi, an island located approximately 500 kilometres east of Darwin and 250 kilometres west of Nhulunbuy, is approximately half a kilometre off the mainland and forms part of the Crocodile Island Group. A Methodist Overseas Mission was established there in 1923. The two main languages are Gupapuynu and Djambarrpuynu, and English is a second language for most Aboriginal residents. It is the birthplace of noted didjeridu maker and player Djalu Gurruwiwi. Milingimbi is probably Djinan in origin from Milininbi, literally ‘the place where the well is’. The original owners were Yan-nhanu speaking clans.

History

There have been many outside influences of Arnhem Land culture, in the form of Balanda4 settlement and, prior to this, communication with the Macassan5 fisherman from the southern tip of Sulawesi. The Macassans traded with Aboriginal groups across the top end, particularly in eastern Arnhem Land. Historically, the Macassans came south on the northwest monsoon winds in December, to collect trepang (beche-de-mer), a sea slug, which they dried and traded with the Chinese, returning home to Indonesia in March and April on the southeast trade winds. It is thought that the trading commenced sometime between 1100 and 1600.

The relation between the Yolngu6 and Macassans, particularly in eastern Arnhem Land, resulted in the Yolngu incorporating the Macassans into their kinship and cosmology. This relationship was to cease in 1906, prohibited by the Australian Government Immigration Act, but is still celebrated through bark painting such as Sam Baramba Wurramara ‘s Macassan prau in the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Gunbalanya, sometimes spelt Kunbarlanja, (Oenpelli), closest to the present day location of Kakadu, and to Darwin, was where Kuninjku people first experienced contact with non-indigenous people, who included anthropologists, collectors and traders. In 1912 anthropologist Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer came to study the region ‘s wealth of artistic expression. Spencer and Paddy Cahill, who had established Gunbalanya in 1906, together commissioning over 200 bark paintings for the Melbourne Museum in exchange for sticks of tobacco.7

The next influence was that of the missionaries lead by the Methodist Overseas Mission, establishing in 1916, the early mission stations at Warruwi (Goulburn Island); Minjilang, Croker Island in 1941; Maningrida in 1957; Milingimbi mission in central Arnhem Land in 1923; Yirrkala in 1935; and then Galiwin’ku, Elcho Island in 1942. A mission was formed at Gunbalanya, the site of Paddy Cahill’s8 pastoral lease, and later a mission was established at Umbakumba on Ayangkulyumuda, (Groote Eylandt) in 1958 for the local Warnindilyakwa people. Missions provided a central location for the various clan groups encouraged by the availability of food and medicine. Missions also support the production of art for the small, but growing industry.

However, the Catholic Mission, established in 1935 at Wadeye (Port Keats) implemented restrictions in regard to cultural practice. The bark paintings of the Wadeye region, feature broad fields of ochre, which were accentuated by a perimeter of white dots containing figuration, resulting in the open landscape that is particular to style of this region.

In 1931, Arnhem Land was declared a reserve for Aboriginal people. Towns and service centres grew from original government settlements and mission stations. During 1962-3, the senior clan leaders of the Yirritja and Dhuwa moieties9 of Eastern Arnhem Land were each responsible for the creation of a substantial panel to show the descent of contemporary Yolngu10 from the Ancient Beings; each panel to be installed on either side of the cross in the new Methodist Mission church at Yirrkala.

Certainly amongst the most important art works produced in Australia, these barks, known as the Church Panels were an affirmation that there were no inherent incompatibilities between Christian and Yolngu beliefs. However, in the 1970s, a new minister viewed them as dangerously heathen and they were removed and stored in a shed. They are now displayed in a special room at Buku Larrgay Mulka Centre at Yirrkala.

Despite the 1931 Act returning Arnhem Land to Aboriginal people, and the lack of dialogue with the local people, the Federal Government excised an area of land around the Mission at Yirrkala, for a French company to mine bauxite. The Yolngu response, a petition in two parts representing both the Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties, consisting of a respectfully and directly worded document written in both English and a Yolngu language addressed to the Federal Parliament, was historic. Known as the Bark Petition, these two barks remain on pubic display at Parliament House and have been described as Australia’s Magna Carta.

With the passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act in 1976, there was an exodus from mission and government centres such as Maningrida, to outstations within the Aboriginal peoples ‘homelands’.

Art and the Art Centres

It is almost impossible to understand bark painting without a comprehension of rock art, and it is estimated that there are over 5,000 individual rock sites within the World Heritage Kakadu National Park, making it one of the most concentrated regions in the world, with some sites possibly more than 18,000 years old. A current view is that rock painting has evolved through different periods, which have included the x-ray style and the most recent period and may have reflected changes in environmental conditions.11

In Western Arnhem Land, in the more recent examples, paintings have been attributed to Najombolmi, and to his relatives who all have followed the stylistic traditions of their predecessors. These particular images depict many precise anatomical features of animal and human which include back bone and the long bones, internal organs such as the lungs, heart, liver and kidneys; human tissue including fat, muscles and flesh; body cavities and fluids. Contrary to popular opinion, colours were not restricted to the basic ochres, with purple, pink, orange and blue being evident.

In Western Arnhem Land, in the more recent examples, paintings have been attributed to Najombolmi, and to his relatives who all have followed the stylistic traditions of their predecessors. These particular images depict many precise anatomical features of animal and human which include back bone and the long bones, internal organs such as the lungs, heart, liver and kidneys; human tissue including fat, muscles and flesh; body cavities and fluids. Contrary to popular opinion, colours were not restricted to the basic ochres, with purple, pink, orange and blue being evident.

A varied form of stick figures also feature in rock painting, which were static or alternatively, in rather expressive poses suggesting action. In some areas there are complex groups including warfare like postures with figures holding spears and appearing to throw spears. Some figures however, were depicted in domestic, ceremonial and hunting scenes appearing more casual.

Image: DJAWIDA NADJONGORLE 1943 –, Mimih Spirits c.1972, natural pigments on bark, © the artist, courtesy Injalak Art Centre.

Some of the larger figures are believed to represent Spiritual Beings, particularly the

mimih which are tall, thin figures who inhabited the sandstone country, easily able to slip in and out of the cracks in the rocks. While the image has been recreated onto bark, Crusoe Guningbal (also Kuningbal) is the first artist to create the mimih in a nonceremonial sculptured form, with a commercial market in mind.

Many of the rock paintings of animals such as kangaroos and fish, appear to have been executed after hunting and fishing, rather than painted before as hunting magic. Often animal paintings were used to instruct and pass on traditional practices and beliefs.

Arnhem Land is particularly known for its bark paintings. The bark is cut and then peeled from trees during or at the end of the wet season, when the sap rises up the tree ensuring the bark is flexible. It is flattened, placed over coals of a fire to steam out the moisture, then laid out in the sun weighted down with stones to dry. After this, the inner surface is rubbed smooth and the outer charred material removed. Traditionally earth ochres and binder, usually orchid juice, mixed together on a stone were applied with sticks, reeds and brushes made from hair, some as thin as only a few strands. Today, wood glue may be used as a binder with commercial brushes to apply the ochre. It is difficult to date the practice of painting on bark as it is not a permanent form like rock art. Painting on bark for an economic art market expanded in the late 1950s and again in the 1970s.

However, bark painting has enjoyed a tradition in many parts of the continent, with the first account dating from a French discovery voyage between 1800 and 1804, at Maria Island, Tasmania.12 There are a number of other Tasmanian accounts of bark shelters adorned with drawings, dating from the early 1880s. Unfortunately, none of these have survived. It is also known that painting on bark was practised in Victoria and New South Wales, and barks have been collected in the Kimberley. However, it is in Arnhem Land and adjacent islands that bark painting flourished and where the art form continues uninterrupted to contemporary times.

Bark paintings from Western Arnhem Land tend towards more naturalistic images, often on a plain red background and follows the x-ray and mimih styles of rock painting; while the east makes more use of geometric patterning, especially cross hatching (rarrk), which is believed to be strongly connected to body paint designs. 13 The striking feature of the Eastern Arnhem Land style, is the intricate compositions of figures placed within a refined patterned background. Blank spaces are not aesthetically pleasing to these artists. The Yolngu of Eastern Arnhem Land, reflect in their painting, the creative activities of the Spiritual Beings who created their universe in its full breadth – the sea, land, flora, fauna and humanity. Essentially, Yolngu art is religious, as it is linked to the Wangarr (the Ancestral past) and forms part of ritual activities. The Ancestral Beings were the first to create paintings and passed on the activity to the human beings, the next inhabitants of the land. Frequently the imagery or design evolved as a result of an Ancestral event. Examples of this include the diamond design which the Mardarpa clan use, particularly in regard to Bara, the crocodile. It is said that the design represents the pattern on Bara’s back, which came about by his burning bark shelter collapsing on him. The Yolngu believe that in re-creating these sacred designs, they are securing a part of the Dreaming.

The geometric design has ownership of particular places and or events that have taken place, revealing how happenings shaped and explained the world and its geographic features. It is usual that the design will identify the particular clan, perhaps the painter and a certain area of land. Painting is the medium to both transmit religious knowledge and to transfer spiritual power on a generational basis. Painting is part of the continuing of Ancestral practices and the nature of the painting will reflect the significance of the person and the purpose of the ceremony. Significant ceremonies include circumcision and death, especially if the individual has been a powerful person.

The geometric design has ownership of particular places and or events that have taken place, revealing how happenings shaped and explained the world and its geographic features. It is usual that the design will identify the particular clan, perhaps the painter and a certain area of land. Painting is the medium to both transmit religious knowledge and to transfer spiritual power on a generational basis. Painting is part of the continuing of Ancestral practices and the nature of the painting will reflect the significance of the person and the purpose of the ceremony. Significant ceremonies include circumcision and death, especially if the individual has been a powerful person.

Significant Creation Stories

Two of the most celebrated creation stories are that of the Djang ‘kawu creators and the Wagilag Sisters, both of great significance to the Dhuwa Moiety. The Djang ‘kawu, owned by the coastal clans, concerns the saga of two sisters and a brother, birth, their cultural values and characteristics.

Image: DAWIDI DJULWAK 1921 -1970, Wagilag Sisters, natural pigments on bark, © the artist Courtesy Bula ‘Bula Arts.

The Wagilag Sisters

In essence, the Wagilag Sisters is a narrative that accounts for the first encounter of human and animal ancestors. It deals with many key aspects of Yolngu social life and the accompanying rituals, which are expressed in ceremony and through the laws pertaining to authority, kinship, marriage and territory.

The story encompasses several language groups and clans and does vary from clan to clan and narrator but deals mostly with the inland freshwater country. In 1997, the 8 National Gallery of Australia held the exhibition The Painters of the Wagilag Sisters Story 1937-1997, and we recommend the catalogue for further in-depth reading. 14

Anthropologists have played a significant role both through their activities, especially within Eastern Arnhem Land and as collectors of important bark paintings and sculptures. Ronald and Catherine Berndt worked at Milingimbi and Yirrkala immediately post war, and were followed in 1948 by Charles P. Mountford and the AmericanAustralian Scientific Expedition, which visited Gunbalanya (Oenpelli), Milingimbi, Yirrkala and Groote Island. From 1965 to 1970, Helen Groger-Wurm from the Aboriginal Institute of Aboriginal Studies, undertook field work in Arnhem Land.

Other significant art produced in northern Australia include painted hollow logs, funeral vessels with exterior decoration depicting relevant totems and clan designs; wooden sculpted and painted spirit figures; Morning Star poles decorated with ochres and feathers and coloured string;15 ceremonial fibre arts, practical forms such as woven bags and sculpture pieces in the form of animals. Much art of the Tiwi art from Bathurst and Melville Island relates to funeral rites, particularly the Pukumani ceremony and the carved wooden cemetery poles. 16

The Association of Northern Kimberley Australian Aboriginal Artists (ANKAAA, established in 1987) maintains its function to foster the Aboriginal arts industry for the benefit of Aboriginal owned and controlled community arts and crafts organisations and by 2009 represented over 2,500 artists from the Tiwi Island, Darwin, Katherine, the Kimberley and Arnhem Land regions.

Further References

Aboriginal Arts Board, Oenpelli Bark Painting, Ure Smith, 1979

Ancestral power and the aesthetic: Arnhem Land paintings and objects from the Donald

Thomson Collection, Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2009

Armstrong, Claire, (ed.) Australian Indigenous Art Collection: Commande Publique

D’Art Aborigène Musée Du Quai Branly, Art & Australia, Sydney 2006

Art and Place: Collecting contemporary art at Northern Territory University, Northern

Territory University, Darwin, 1999

Australian Aboriginal Art, an exhibition arranged by the State Art Galleries 1960-1961

Australian Bark Painting, from the collection of Dr Edward la Ruhe, exhibition catalogue,

Meadow Brook Art Gallery, Michigan, USA, 1999

Bardley, L., Mellor, D., and Rose, D. B., Claiming Title: Australian Aboriginal Artists and

the land, Carlton College Art Gallery, Northfield, USA, 1999

Bark Paintings of Western Arnhem Land, exhibition catalogue, Holmes à Court Gallery,

Perth, 2000

Berndt, R. M. and Berndt, C. H., with Stanton, John, E., Aboriginal Australian Art: A

Visual Perspective, Metheum Australia, Melbourne, 1982

Berndt, R. M., Djanggawul: An Aboriginal religious cult of north-eastern Arnhem Land,

Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd, London, 1952

Berndt, R. M. and Berndt, C. H., Man, Land and Myth in Northern Australia: The

Gunwinggu People, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1970

Brody, A., Kunwinjku Bim: Western Arnhem Land Paintings from the collection of the

Aboriginal Arts Board, National Gallery of Victoria, 1984

Caglayan, Emily Rekow, The sacred revealed: An iconographic study of the Berndt

Collection of Arnhem Land bark paintings at the American Museum of Natural History,

Thesis (Ph.D.), City University of New York, 2005

Carew, M., Men of High Degree, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Victoria,

Melbourne, 1997

Caruana, Wally, Aboriginal Art, Thames & Hudson, London, 2003, see chapter 2

Caruana, Wally, and Lendon, Nigel, The Painters of the Wagilag Sisters Story 1937-

1997, National Gallery of Australia, 1997

Caruana, Wally (ed.), Windows on the Dreaming: Aboriginal paintings in the Australian

National Gallery, Australian National Gallery and Ellsyd Press, Sydney, 1989

Croft, Brenda L., Indigenous Art: Art Gallery of Western Australia, Art Gallery of

Western Australia, Perth, 2001

Crossing Country The Alchemy of Western Arnhem Land Art, Art Gallery of New South

Wales, 2004

Davidson, James, Aboriginal and Oceanic Decorative Art, National Gallery of Victoria,

1980

Diggins, Lauraine, (ed.), A Myriad of Dreaming: Twentieth Century Aboriginal Art,

Malakoff Fine Art Press, 1989, pp. 15 – 39

Ducreux, Anne- Clair, Apolline, Kohen and Salmon, Fiona, In the Heart of Arnhem Land,

Myth and the Making of Contemporary Art, exhibition catalogue, Musée del l ‘Hotel-Dieu,

Mantes-la-jolie, France, 2001

Edwards, M. (ed.), Banumbirr (catalogue), Elcho Island Art and Craft and Bandigan

Aboriginal Art and Craft, 2002

Edwards, Robert (ed.), Aboriginal Art in Australia, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1978

Edwards, Robert (ed.), ‘The Preservation of Australia ‘s Aboriginal Heritage’, Australian

Aboriginal Studies, No.54, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1975

Edwards, R. & Guerin, B., Aboriginal Bark Paintings, Rigby, 1969

Ellwood, Tony (ed.), Floating Life: Contemporary Aboriginal Fibre Art, Queensland Art

Gallery, 2009

Groger-Wurm, Helen, Australian Aboriginal Bark Paintings and their Mythological

Interpretation: Eastern Arnhem Land, vol 1, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies,

Canberra, 1973

Hamby, L. (ed.), Fibre Art from Elcho Island (exhibition catalogue), University of New

South Wales, 1994

Holmes, Sandra, Yirawala: Artist and Man, Jacaranda Press, Brisbane, 1972

Holmes, Sandra, Yirawala: Painter of the Dreaming, Sydney, 1992

D. Carment et al, Northern Territory Dictionary of Biography, vol 1 (Darwin, 1990);

Aboriginal News, 3, no 1, Feb 1976.

Horton, David (ed.), The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia, Aboriginal Studies Press

for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra,

1994

Investigating Key Artworks In The Gallery www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/education

Isaacs, Jennifer, Spirit Country: Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art, Hardie Grant

Books, 1999, see pp155 – 226

Issacs, Jennifer, Wandjuk Marika: Life Story, University of Queensland Press, 1995

Jones, Jonathan, Mountford gifts, online exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 2009

Kleinert, Sylvia & Neale, Margo (general eds.), The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art

and Culture, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp.129 – 179

Kupka, Karel, Dawn of Art: Painting and Sculpture of Australian Aborigines, Angus and

Robertson, 1963

Laverty, Colin, Beyond Sacred: Recent paintings from Australia’s Aboriginal

communities. The Collection of Colin and Elizabeth Laverty, Hardie Grant Books,

Melbourne, 2008

Le Brun Holmes, S., Yirawala: Artist and Man, Jacaranda Press, Sydney, 1972

Lock-Weir, Tracy, Art of Arnhem Land 1940s-1970s, Art Gallery of South Australia,

2002

Loveday, P. and Cooke, P. (eds.), Aboriginal Arts and Crafts and the Market, North

Australian Research Unit, Darwin, 1983

Lüthi, Bernhard (ed.), Aratjara – Art of the First Australians: Traditional and

contemporary works by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists, exhibition

catalogue, Kunstsammlung Nordhein – Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 1993

McCarthy, Federick D., Australian Aboriginal Rock Art, Australian Museum, Sydney,

1958

Meeuwsen, Franca, Aboriginal Kunst: de verhalen vertellen, Aboriginal Art Museum,

Utrecht, 2000

Morphy, Howard, Ancestral Connections: Art and Aboriginal systems of knowledge,

University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1991

Morphy, Howard and Smith Boles, Margot (eds.), Art from the Land: Dialogues with the

Kluge-Ruhe collections of Australian Aboriginal art, University of Virginia,

Charlottesville, Virginia, 1999

Mosby, Tom, Ilan Pasin Torres Strait Art, Cairns Regional Gallery, 1998

Mulvaney, J., Paddy Cahil of Oenpelli, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2004

Mulvaney, John and Calaby, J. H., So much that is new: Baldwin Spencer, 1860-1929,

a biography, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1985

Murphy, Bernice (ed.), The Native Born: Objects and representations from Ramingining,

Arnhem Land, Museum of Contemporary Art, 1996

Nicholls, Christine, An Individual Perspective: From the Indigenous Collection of

Lauraine Diggins, Deakin University, 2009

Nicholls, C., Espiritualidad y Arte Aborigen Australiano, Communidad de Madrid,

Madrid, 2001

Normand, Simon, Stonecountry to Saltwater: recent artwork & stories from Ngukurr,

Arnhem Land, 2009

O ‘Ferrall, M. A., Keepers of the Secrets: Aboriginal art from Arnhem Land in the

collection of the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Art Gallery of Western Australia,

Perth, 1990

One Sun, One Moon: Indigenous art in Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales,

Sydney, 2007

Porta oberta al Dreamtime: Art Aborigen Contemporani D’ Australia, Fundacio Caixa de

Girona, Girona, Spain, 2004

Ryan, Judith, Spirit in Land: bark paintings from Arnhem Land, National Gallery of

Victoria, 1990

Ryan, Judith, ?Tradition and Transformation: Ochre Art Forms of Arnhem Land ‘, in Ryan,

Judith (ed.), Land Marks, National Gallery of Victoria, 2006

Saldais, Maggie & Leary Karen, (ed.) Marking Our Time: Selected Works of the Art

from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collection at the Nationa Gallery of

Australia, Thames and Hudson, Melbourne, 1996

Stubbs, Dacre, Prehistoric Art of Australia, The Macmillian Company of Australia, South

Melbourne, 1974

Sutton, Peter, Dreamings: The art of Aboriginal Australia, Viking, in association with The

Asia Society Galleries, New York, 1988

Saltwater: Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country, Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, 1999

Taçon, Paul S. C. Enduring Rock Art: Ancient Traditions, Contemporary Expressions ‘,

in Ryan, Judith (ed.), Land Marks, National Gallery of Victoria, 2006

Taylor, Luke, Seeing the Inside: Bark Painting in Western Arnhem Land, Clarendon

Press, Oxford, 1996

Thomson of Arnhem Land Film telling the story of Australian anthropologist,

photographer and journalist, Donald Thomson and his lifelong struggle for Aboriginal

rights.

Tradition today: Indigenous art in Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney,

2007

Ucko, Peter J. (ed.), Form in Indigenous Art: Schematisation in the art of Aboriginal

Australia and prehistoric Europe, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra,

1977

Vanderwal, Ron (ed.), The Aboriginal Photographs of Baldwin Spencer, Viking

O ‘Neil,1982

Wells, Ann E., Milingimbi, Ten Years in the Crocodile Islands of Arnhem Land, Angus

and Robertson, Sydney, 1963

West, M., Rainbow, Sugarbag and Moon: Two artists of the stone country, Bardayal

Nadjamerrek and Mick Kubarkku, exhibition catalogue, Museum and Art Gallery of the

Northern Territory, Darwin, 1995

West, M., The Inspired Dream, Life as Art in Aboriginal Australia, exhibition catalogue,

Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1988

West, Margie (ed.), Yalangbara: art of the Djang’kawu, produced in partnership with

Banduk Marika and other members of the Rirratjingu clan, north-east Arnhem Land,

Charles Darwin University Press, 2008

Wright, Felicity, Good Stories from the Bush: Examples of best practice from Aboriginal

art and craft centres in remote Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Commission, Canberra, 2000

Yunupingu, Galarrwuy, ?The Black/White Conflict ‘ in Caruana, Wally (ed.), Windows on

the Dreaming: Aboriginal Paintings in the Australian National Gallery, Sydney, 1989

Jilamara Arts & Crafts, jilamara.com

Maningrida Arts & Culture, maningrida.com

Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre and Museum, yirrkala.com

Sugarbag (Australia ‘s stingless native bees), sugarbag.net

Twelve Canoes, 12canoes.com.au

Foot Notes

1. Groger-Wurn. H., Australian Aboriginal Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1973, p. 11. ↩

2. The dugong is the only strictly marine herbivorous mammal. ↩

3. The policy of forceful removal of indigenous children from their families. ↩

4. Term for white or European person. ↩

5. Fishermen and traders from Sulawesi in Indonesia, who visited the northern shores of the continent until

the early twentieth century. ↩

6. Term to describe Aboriginal people of central and eastern Arnhem Land. ↩

7. Investigating Key Artworks In The Gallery. ↩

8. Paddy Cahill was one of the first buffalo shooters in Western Arnhem Land. He took out a dairy lease on the present site of Gunbalanya and established a farm growing fruit, vegetables and cotton. He developed a deep interest and empathy with Aboriginal people. ↩

9. A pair of complementary social and religious categories. ↩

10. Term to describe Aboriginal people of Central and Eastern Arnhem Land. ↩

11. West, Margi, Ed., The Inspired Dream, Queensland Art Gallery, 1988. ↩

12. Groger-Wurn. H., Australian Aboriginal Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1973. ↩

13. Cross hatch patterning, usually found painted on barks of Arnhem Land and can be read to identify different clans of Arnhem Land (known as dhulang in north-east Arnhem Land; dirrnu in Wadeye region; miny ‘tji in central and north eastern Arnhem Land. ↩

14. See details in Further Reading at conclusion.↩

15. These are used by performers in a Morning Star burial ceremonies whereby the Morning Star connects the feathered string to the deceased ‘s soul to guide it to the Land of the Dead. ↩

16. Term associated with burial rites of Tiwi people. ↩