The Torres Strait is a body of water that lies between Cape York Peninsula, at the tip of Northern Queensland, and Papua New Guinea. The Strait encompasses at least 270 islands with seventeen permanent settlements with a population of just over eight thousand residents. Torres Strait Islanders are related to the Papuans of New Guinea and they share a longstanding history of trade and culture.

The eastern islands within the Torres Strait have rich and fertile land surrounded by extensive mangroves and weathered granite rocks. The islands are large, but are surrounded by shallow seas and sandbanks, allowing easy access between the islands for generations. The central islands are small low-lying coral islands, surrounded by vast reefs, which are known for causing havoc for larger ships.

Image: The Torres Strait, © image courtesy of Valentine Kalwij

Language and Clans

The Torres Strait, like many mainland Indigenous Australian cultures, is traditionally an oral culture where song, myth and belief are passed down verbally through the generations.

There are two languages spoken by Torres Strait Islanders. In the Eastern Islands the traditional language is Meriam Mir, spoken on the islands of Ugar (Stephen Island), Erub (Darnley Island) and Mer (Murray Island). The Western and Central Island groups, consisting of Boigu (Talbot Island), Dauan (Mount Cornwallis), Saibai, Mabuiag (Jervis Island), Badu (Mulgrave Island), Moa (Banks Island), Iama (Yam or Turtle-backed Island), Warraber (Sue Island), Poruma (Coconut Island) and Masig (Yorke Island) speak Kala Lagaw Ya.

The Kala Lagaw Ya language itself has four dialects – Kulkalgaw Ya, Mabuiag, Kawrareg and Kala Kawaw Ya. The four dialects originate from the Central Islands; Mabuaig, Moa and Badu Islands; the Muralag Group and Top Western Islands respectively.

Most Islanders also speak a mixture of traditional languages and English called Torres Strait Creole. Recently, it has been proposed to name this language Yumiplatok (meaning ‘you me fella talk’) to distinguish it from other creole languages.

History

Archaeological research has indicated human settlement in the Torres Strait dating back 2,500 years. The earliest interaction with non-Islander peoples was with the neighbouring cultural groups of Australia and Papua New Guinea. There is also some indication that Macassans travelled from Indonesia for the bêche-de-mer (sea slug) hunting season.

The first European interaction with the islands was made in the early seventeenth century. The first recorded contact was made by the Dutch yacht Duyfhen that sailed from Bantam to explore New Guinea in 1605. A Spanish captain, Luis Vaz de Torres, for which the Strait derives its name, also sailed through the area in 1606 on his way to Manila. His letters to the King of Spain regarding the islands were rediscovered by the Scottish geographer Alexander Dalrymple in 1769, who named the islands after Torres. The discovery of the islands contributed to widespread interest in establishing an expedition to the area, an expedition was eventually led by Captain James Cook in 1770.

The voyages of William Bligh and Matthew Flinders also sailed though the Torres Strait in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, which gave many of the islands their European names. During the later half of the nineteenth century several ships passed through the Torres Strait from the east coast of Australia to Asia. Interaction with the inhabitants was limited, with only a small number of these ships conducting trade with the islanders. European objects – such as iron knives, ships’ biscuits, tobacco and bottles – were present on the islands in the mid nineteenth century.

Greater interaction with European traders occurred as part of the pearlshelling trade. In 1869, Tudu Islanders (Warrior Islanders) showed ‘Tongutapu Joe’, a Pacific Islander working on a bêche-de-mer (sea slug) boat, about an area of pearlshell on the Warrior Reefs. Following this discovery, a number of Pacific Islander boats arrived to the Torres Strait to take advantage of the profitable commodity. Within three years, five hundred Pacific Islanders were working on pearling boats in the Torres Strait. The trade also brought experienced divers from many countries, including Japan.

The involvement of Torres Strait Islanders in the pearling trade began immediately. By 1870, Marus, the chief of Ugar (now Stephen Island), had visited Sydney twice and others had visited the south east coast of Australia with boat owners. These men spoke some English which was eventually incorporated in the Pacific Pidgin English of the Pacific Islander workers, creating Torres Strait Creole.

Christianity arrived in the Torres Strait with the London Missionary Society on 1 July 1871, a day that is celebrated as an annual holiday in the Strait. Today, many Torres Strait Islanders divide their history into the ‘time before’ (Pre-Christian) and the ‘time after’ period beginning from this date, 1 July 1871. By 1890 an almost complete conversion to Christianity had occurred.

Image: C. M. Yonge, Church and congregation, Meer Island, Queensland, c.1928, National Library of Australia PIC/11204/217

The colony of Queensland annexed islands in The Torres Strait during the late 1870s, with complete annexation occurring in 1879 by an Act in the Legislative Assembly in Brisbane.

In 1904 the Torres Strait was incorporated under the Queensland Aborigines Protection Act (1897), which placed a strict regime on Islander activities including restrictions on inter-racial marriage. Many families of mixed descent were resettled on Moa and Kiriri Islands. The governance at this time had a lasting effect by creating a more homogenous Torres Strait culture. The power held by the government Protector included the control of the wages earned by Islanders on boats, a grievance which contributed to a strike of approximately seventy percent of the Islander workforce in 1936.

In 1898, British anthropologist and ethnologist Alfred Haddon undertook fieldwork in the Torres Strait. Haddon acquired a large collection of ethnographical objects, which are now in the British Museum and the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge. Haddon also collected rare film footage of ceremonial dances.

In the steps of Alfred Haddon, anthropologist Margaret Lawrie visited the area between 1960 and 1973 and gathered information about the local mythology, languages, history, art and culture. Lawrie also undertook extensive recording of oral histories for the Australia Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Her studies included illustrations completed by Torres Strait Islanders in a naïve realist style, produced after she provided them with watercolours and paper.

Art and the Art Centre

The art from the Torres Strait Islands is stylistically distinct from that of mainland Indigenous Australia. The characteristics of Torres Strait Islander art are more akin to the art of its immediate neighbours in Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands. The immediate environment provided the materials for Torres Strait art practice, specifically pearls, turtle-shell, wood, feather and coconut leaves.

Image: RICARDO IDAGI 1957-, Malora Kub (flanked by two Beizam Tirig and eight Dari headdresses) mixed media, © the artist

The introduction of development of Christianity also had a profound influence upon the art and culture of Torres Strait. The missionaries restricted some aspects of the Torres Strait song and dance and condoned others. The traditional artforms of sculpture, costume and jewellery are intrinsically linked to ceremony, dance and song and were altered by these changes. The Anglican Church assumed responsibility for the islands in 1915 and incorporated a number of island customs into Christian practice allowing for a greater freedom of expression.

The artists of the Torres Strait Islands are well known for the creation of traditional masks and headdresses. One artform that remained in use throughout the Torres Strait is the dhoeri or dari, the headdress worn by men during dance performances. These headdresses typically take the form of a cane structure with a halo of white feathers which frame the face. The masks are used in mortuary and initiation ceremonies. The creation of masks is traditionally the domain of men, but the creation of woven objects was the preoccupation of women. The arrival of the Pacific Islander missionaries introduced Islander women to the weaving techniques of the Pacific Islands.

Torres Strait artists have been divided into three groups: traditional community, urban and traditional urban. The first of these groups are those artists who produce art within established cultural frameworks and generally reside within the Torres Strait, including James Eseli, Freddy and Gada Nai, Charles Warusam, Richard Harry, Mary Betty Harris and Jenny Mye. Urban artists practice with reference to concepts of Western art such as individual expression, and include artists such as Ellen Jose, Clinton Nain and Lisa Martin.

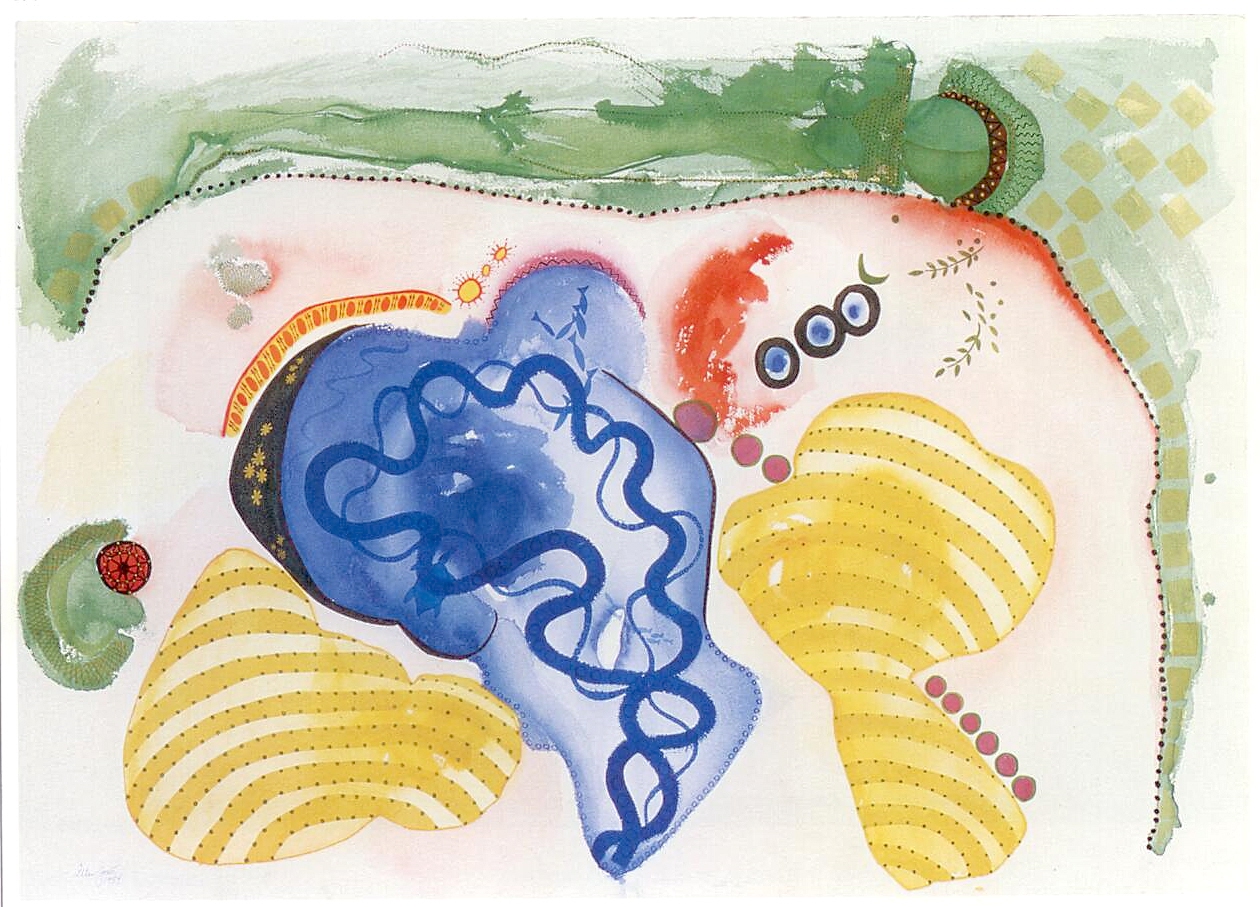

Image: ELLEN JOSE 1951-, Woman – Landscape, 1989, watercolour on paper, © the artist

The traditional urban artists experiment with Western art techniques but also practice within the realm of communal art practices. Ricardo Idagi, a Melbourne-based multi disciplinary artist, received his cultural education from family while living on Mer (Murray Island) and in Townsville, and received art training in Cairns, before settling in Melbourne in 1997. Another prominent example of this type of artist is Dennis Nona, who creates works with traditional designs and symbols, but in non-traditional mediums such as lithography and metalwork.

Printmaking is a more recent artform used by Torres Strait artists. Although two-dimensional art was created under the guidance of anthropologist Margaret Lawrie, traditionally it was confined to body decoration. The use of the print mediums is directly related to the Printmaking course at the Department of the Faculty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies at the Tropical North Queensland Institute of TAFE, Cairns, which many artists attended. The establishment of the TAFE art school in Cairns in 1984 provided opportunities for many Torres Strait Islander artists to gain artistic training and support.

The Gab Titui Cultural Centre, which was established in 2004, was named by the former cultural advisor Ephraim Bani. The word ‘Gab’ means journey in the eastern island group language and ‘Titui’ means stars in the western islands group. The name of the art centre is therefore translated as ‘Journey of the Stars’ and represents the unity of the different areas of the Torres Strait. The centre is responsible for both the development and preservation of Torres Strait culture and its remit encompasses both historical artefacts and contemporary Indigenous art.

In addition to the Gab Titui Cultural Centre, there are other independent art centres based in the Torres Strait: Badhulgaw Kuthinaw Mudh on Badu Island (Mulgrave Island), Erub Erwer Meta located on Erub (Darnley Island) and Ngalmun Lagau Minaral on Moa Island.

Significant Creation Stories

Torres Strait Islander history accounts for the beginning of the islands. ‘In the beginning…Pop appeared and had the island to himself’.1 Pop created a companion in the shape of a female dugong with human legs out of white mud. He then coughed into the mouth of the figure, bringing her to life.

Torres Strait Islander histories have a number of accounts of the population of the islands. In one instance, three women came from Op Deudai (Papua New Guinea) and were shipwrecked separately on the islands of Mer (Murray Island) and Erub (Darnley Island). Three men from Op Deudai found the stranded women and settled on the islands where they had children.

Another account tells of the men of Boigu who lived on the island without women. There were women living on Op Deudai who climbed over a bamboo plant to Boigu Island and married the men. Other origin stories described the coming of light-skinned men.

The Four Seasons

The mythology of the people of the Torres Strait is connected to the land, sea and sky, and these themes are interwoven in spiritual beliefs, stories, songs and dances. The four seasons are associated with the wind changes in the environment – Kuki, Sager, Zey and Nay Gay.

Kuki is associated with the northwest winds that blow during the wet season from January to April and Sager is related to the southeast trade winds during the dry season from May until December. Zey are the southerly winds which blow intermittently throughout the year and Nay Gay are the northerly winds which blow when the weather is at its hottest and most humid, typically from October to December.2

Artists: Past and Present

| Aaron Armitage | Joseph Au | Aunty Milly |

| Maryanne Bourne | Solomon Booth | James Eseli |

| Iona Gaidan Senior | Sarah Gaidan | Tala Gaidan |

| Zacharia Gaidan | Emma Gela | Pinau Ghee |

| Florence Gutchen | Kapua Gutchen | Mary Betty Harris |

| Richard Harry | Flora Joe | Ellen Jose |

| Job Kusu | Edmund Laza | Mengui Manoa |

| Lisa Martin | Weldon Matasia | Victor Motlop |

| Frank Mye | Jenny Mye | Freddy Nai |

| Gada Nai | Alice Namok | Clinton Nain |

| Dennis Nona | Gehmat Nona | Jomen Nona |

| Michael Nona | Tipoti Nona | Laurie Nona |

| Racy Oui-Pitt | Ellarose Savage | Sedey Stephen |

| Jimmy Thaiday | Ken Thaiday | Sweeney Thaiday |

| Alick Tipoti | Angela Torenbeek | Sarah Ven Hooran |

| Charles Warusam |

Further References

Brady, Liam M Pictures, patterns & objects: rock-art of the Torres Strait Islands, Northeastern Australia. North Melbourne, Vic. Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, 2010.

Caruana, Wally and Cubillo, Franchesca, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander art: collection highlights, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2010.

McCulloch, Susan and McCulloch Childs, Emily, McCulloch’s contemporary Aboriginal art: the complete guide. McCulloch & McCulloch, Carlton, 2008.

Mosby, Tom Ilan Pasin – This is our way, Cairns Regional Art Gallery, 1998

Art Gallery of New South Wales and Neale, Margo Yiribana: an introduction to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1994.

O’Connell, Rae, et al. Ailan currents: contemporary printmaking from the Torres Strait. KickArts Contemporary Arts, Cairns, 2007.

Queensland Indigenous Arts Marketing and Export Agency, Power in art: contemporary expressions from leading Indigenous artists of Queensland, Australia, QIAMEA, 2008.

Philp, Jude, Past time: Torres Strait Islander material from the Haddon Collection, 1888-1905: a National Museum of Australia exhibition from the University of Cambridge. National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2001.

Ryan, Judith. Indigenous Australian art: in the National Gallery of Victoria. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2002.

Ryan, Judith et al. Raiki wara: long cloth from Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1998.

Taylor, Luke, Painting the land story, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 1999.

Foot Notes

1. Mosby, Ilan Pasin, p. 17↩

2. Tom Mosby, Ilan Pasin – This is our way, Cairns Regional Art Gallery, 1998. ↩